Domain classes are core to any business application. They hold state about business processes and hopefully also implement behavior. They are linked together through relationships, either one-to-one or one-to-many.GORM is Grails' object relational mapping (ORM) implementation. Under the hood it uses Hibernate 3 (an extremely popular and flexible open source ORM solution) but because of the dynamic nature of Groovy, the fact that it supports both static and dynamic typing, and the convention of Grails there is less configuration involved in creating Grails domain classes.You can also write Grails domain classes in Java. See the section on Hibernate Integration for how to write Grails domain classes in Java but still use dynamic persistent methods. Below is a preview of GORM in action:def book = Book.findByTitle("Groovy in Action")book

.addToAuthors(name:"Dierk Koenig")

.addToAuthors(name:"Guillaume LaForge")

.save()grails create-domain-class Person

grails-app/domain/Person.groovy such as the one below:

If you have the dbCreate property set to "update", "create" or "create-drop" on your DataSource, Grails will automatically generated/modify the database tables for you.

You can customize the class by adding properties:class Person {

String name

Integer age

Date lastVisit

}Create

To create a domain class use the Groovy new operator, set its properties and call save:def p = new Person(name:"Fred", age:40, lastVisit:new Date())

p.save()

Read

Grails transparently adds an implicit id property to your domain class which you can use for retrieval:def p = Person.get(1)

assert 1 == p.id

Person object back from the db.Update

To update an instance, set some properties and then simply call save again:def p = Person.get(1)

p.name = "Bob"

p.save()

Delete

To delete an instance use the delete method:def p = Person.get(1)

p.delete()

Book class may have a title, a release date, an ISBN number and so on. The next few sections show how to model the domain in GORM.To create a domain class you can run the create-domain-class target as follows:grails create-domain-class Book

grails-app/domain/Book.groovy:

If you wish to use packages you can move the Book.groovy class into a sub directory under the domain directory and add the appropriate package declaration as per Groovy (and Java's) packaging rules.

The above class will map automatically to a table in the database called book (the same name as the class). This behaviour is customizable through the ORM Domain Specific LanguageNow that you have a domain class you can define its properties as Java types. For example:class Book {

String title

Date releaseDate

String ISBN

}releaseDate maps onto a column release_date. The SQL types are auto-detected from the Java types, but can be customized via Constraints or the ORM DSL.

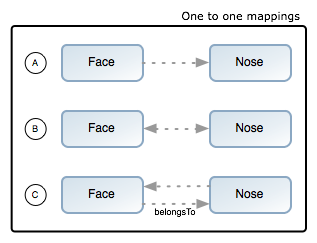

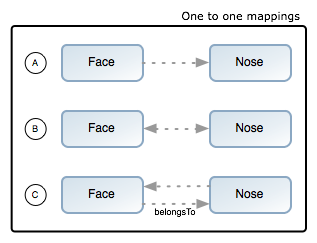

Relationships define how domain classes interact with each other. Unless specified explicitly at both ends, a relationship exists only in the direction it is defined.A one-to-one relationship is the simplest kind, and is defined trivially using a property of the type of another domain class. Consider this example:Example A

class Face {

Nose nose

}

class Nose {

}Face to Nose. To make this relationship bidirectional define the other side as follows:Example B

class Face {

Nose nose

}

class Nose {

Face face

}Example C

class Face {

Nose nose

}

class Nose {

static belongsTo = [face:Face]

}belongsTo setting to say that Nose "belongs to" Face. The result of this is that we can create a Face and save it and the database updates/inserts will be cascaded down to Nose:

new Face(nose:new Nose()).save()

Face:new Nose(face:new Face()).save() // will cause an error

belongsTo is that if you delete a Face instance the Nose will be deleted too:def f = Face.get(1)

f.delete() // both Face and Nose deleted

belongsTo deletes would not be cascading and you would get a foreign key constraint error unless you explicitly deleted the Nose:

// error here without belongsTo

def f = Face.get(1)

f.delete()// no error as we explicitly delete both

def f = Face.get(1)

f.nose.delete()

f.delete()

class Face {

Nose nose

}

class Nose {

static belongsTo = Face

}belongsTo declaration and explicitly naming the association. Grails will assume it is unidirectional. The diagram below summarizes the 3 examples:

A one-to-many relationship is when one class, example

A one-to-many relationship is when one class, example Author, has many instances of a another class, example Book. With Grails you define such a relationship with the hasMany setting:class Author {

static hasMany = [ books : Book ] String name

}

class Book {

String title

}

The ORM DSL allows mapping unidirectional relationships using a foreign key association instead

Grails will automatically inject a property of type java.util.Set into the domain class based on the hasMany setting. This can be used to iterate over the collection:def a = Author.get(1)a.books.each {

println it.title

}

The default fetch strategy used by Grails is "lazy", which means that the collection will be lazily initialized. This can lead to the n+1 problem if you are not careful.If you need "eager" fetching you can use the ORM DSL or specify eager fetching as part of a query

The default cascading behaviour is to cascade saves and updates, but not deletes unless a belongsTo is also specified:class Author {

static hasMany = [ books : Book ] String name

}

class Book {

static belongsTo = [author:Author]

String title

}mappedBy to specify which the collection is mapped:class Airport {

static hasMany = [flights:Flight]

static mappedBy = [flights:"departureAirport"]

}

class Flight {

Airport departureAirport

Airport destinationAirport

}class Airport {

static hasMany = [outboundFlights:Flight, inboundFlights:Flight]

static mappedBy = [outboundFlights:"departureAirport", inboundFlights:"destinationAirport"]

}

class Flight {

Airport departureAirport

Airport destinationAirport

}hasMany on both sides of the relationship and having a belongsTo on the side that owns the relationship:class Book {

static belongsTo = Author

static hasMany = [authors:Author]

String title

}

class Author {

static hasMany = [books:Book]

String name

}Author, takes responsibility for persisting the relationship and is the only side that can cascade saves across.For example this will work and cascade saves:new Author(name:"Stephen King")

.addToBooks(new Book(title:"The Stand"))

.addToBooks(new Book(title:"The Shining"))

.save()

Book and not the authors!new Book(name:"Groovy in Action")

.addToAuthors(new Author(name:"Dierk Koenig"))

.addToAuthors(new Author(name:"Guillaume Laforge"))

.save()

Grails' Scaffolding feature does not currently support many-to-many relationship and hence you must write the code to manage the relationship yourself

As well as association, Grails supports the notion of composition. In this case instead of mapping classes onto separate tables a class can be "embedded" within the current table. For example:class Person {

Address homeAddress

Address workAddress

static embedded = ['homeAddress', 'workAddress']

}

class Address {

String number

String code

}

If you define the Address class in a separate Groovy file in the grails-app/domain directory you will also get an address table. If you don't want this to happen use Groovy's ability to define multiple classes per file and include the Address class below the Person class in the grails-app/domain/Person.groovy file

GORM supports inheritance both from abstract base classes and concrete persistent GORM entities. For example:class Content {

String author

}

class BlogEntry extends Content {

URL url

}

class Book extends Content {

String ISBN

}

class PodCast extends Content {

byte[] audioStream

}Content class and then various child classes with more specific behaviour.Considerations

At the database level Grails by default uses table-per-hierarchy mapping with a discriminator column called class so the parent class (Content) and its sub classes (BlogEntry, Book etc.), share the same table.Table-per-hierarchy mapping has a down side in that you cannot have non-nullable properties with inheritance mapping. An alternative is to use table-per-subclass which can be enabled via the ORM DSLHowever, excessive use of inheritance and table-per-subclass can result in poor query performance due to the excessive use of join queries. In general our advice is if you're going to use inheritance, don't abuse it and don't make your inheritance hierarchy too deep.Polymorphic Queries

The upshot of inheritance is that you get the ability to polymorphically query. For example using the list method on the Content super class will return all sub classes of Content:def content = Content.list() // list all blog entries, books and pod casts

content = Content.findAllByAuthor('Joe Bloggs') // find all by authordef podCasts = PodCast.list() // list only pod castsSets of objects

By default when you define a relationship with GORM it is a java.util.Set which is an unordered collection that cannot contain duplicates. In other words when you have:class Author {

static hasMany = [books:Book]

}java.util.Set. The problem with this is there is no ordering when accessing the collection, which may not be what you want. To get custom ordering you can say that the set is a SortedSet:class Author {

SortedSet books

static hasMany = [books:Book]

}java.util.SortedSet implementation is used which means you have to implement java.lang.Comparable in your Book class:class Book implements Comparable {

String title

Date releaseDate = new Date() int compareTo(obj) {

releaseDate.compareTo(obj.releaseDate)

}

}Lists of objects

If you simply want to be able to keep objects in the order which they were added and to be able to reference them by index like an array you can define your collection type as a List:class Author {

List books

static hasMany = [books:Book]

}author.books[0] // get the first book

books_idx column where it saves the index of the elements in the collection in order to retain this order at the db level.When using a List, elements must be added to the collection before being saved, otherwise Hibernate will throw an exception (org.hibernate.HibernateException: null index column for collection):// This won't work!

def book = new Book(title: 'The Shining')

book.save()

author.addToBooks(book)// Do it this way instead.

def book = new Book(title: 'Misery')

author.addToBooks(book)

author.save()

Maps of Objects

If you want a simple map of string/value pairs GORM can map this with the following:class Author {

Map books // map of ISBN:book names

}def a = new Author()

a.books = ["1590597583":"Grails Book"]

a.save()class Book {

Map authors

static hasMany = [authors:Author]

}def a = new Author(name:"Stephen King")def book = new Book()

book.authors = [stephen:a]

book.save()hasMany property defines the type of the elements within the Map. The keys for the map must be strings.A key thing to remember about Grails is that under the surface Grails is using Hibernate for persistence. If you are coming from a background of using ActiveRecord or iBatis Hibernate's "session" model may feel a little strange.Essentially, Grails automatically binds a Hibernate session to the currently executing request. This allows you to use the save and delete methods as well as other GORM methods transparently.An example of using the save method can be seen below:def p = Person.get(1)

p.save()

def p = Person.get(1)

p.save(flush:true)

def p = Person.get(1)

try {

p.save(flush:true)

}

catch(Exception e) {

// deal with exception

}def p = Person.get(1)

p.delete()

flush argument:def p = Person.get(1)

p.delete(flush:true)

deleteAll method as deleting data is discouraged and can often be avoided through boolean flags/logic.If you really need to batch delete data you can use the executeUpdate method to do batch DML statements:Customer.executeUpdate("delete Customer c where c.name = :oldName", [oldName:"Fred"])belongsTo setting which controls which class "owns" a relationship.Whether it is a one-to-one, one-to-many or many-to-many if you define belongsTo updates and deletes will cascade from the owning class to its possessions (the other side of the relationship).If you do not define belongsTo than no cascades will happen and you will have to manually save each object.Here is an example:class Airport {

String name

static hasMany = [flights:Flight]

}

class Flight {

String number

static belongsTo = [airport:Airport]

}Airport and add some Flights to it I can save the Airport and have the updates cascaded down to each flight, hence saving the whole object graph:new Airport(name:"Gatwick")

.addToFlights(new Flight(number:"BA3430"))

.addToFlights(new Flight(number:"EZ0938"))

.save()

Airport all Flights associated with it will also be deleted:def airport = Airport.findByName("Gatwick")

airport.delete()belongsTo then the above cascading deletion code would not work. To understand this better take a look at the summaries below that describe the default behaviour of GORM with regards to specific associations.Bidirectional one-to-many with belongsTo

class A { static hasMany = [bees:B] }

class B { static belongsTo = [a:A] }belongsTo then the cascade strategy is set to "ALL" for the one side and "NONE" for the many side.Unidirectional one-to-many

class A { static hasMany = [bees:B] }

class B { }Bidirectional one-to-many no belongsTo

class A { static hasMany = [bees:B] }

class B { A a }belongsTo then the cascade strategy is set to "SAVE-UPDATE" for the one side and "NONE" for the many side.Unidirectional One-to-one with belongsTo

class A { }

class B { static belongsTo = [a:A] }belongsTo then the cascade strategy is set to "ALL" for the owning side of the relationship (A->B) and "NONE" from the side that defines the belongsTo (B->A)Note that if you need further control over cascading behaviour, you can use the ORM DSL.Associations in GORM are by default lazy. This is best explained by example:class Airport {

String name

static hasMany = [flights:Flight]

}

class Flight {

String number

static belongsTo = [airport:Airport]

}def airport = Airport.findByName("Gatwick")

airport.flights.each {

println it.name

}Airport instance and then 1 extra query for each iteration over the flights association. In other words you get N+1 queries.This can sometimes be optimal depending on the frequency of use of the association as you may have logic that dictates the associations is only accessed on certain occasions.An alternative is to use eager fetching which can specified as follows:class Airport {

String name

static hasMany = [flights:Flight]

static fetchMode = [flights:"eager"]

}Airport instance and the flights association will be loaded all at once (depending on the mapping). This has the benefit of requiring fewer queries, however should be used carefully as you could load your entire database into memory with too many eager associations.

Associations can also be declared non-lazy using the ORM DSL

Optimistic Locking

By default GORM classes are configured for optimistic locking. Optimistic locking essentially is a feature of Hibernate which involves storing a version number in a special version column in the database.The version column gets read into a version property that contains the current versioned state of persistent instance which you can access:def airport = Airport.get(10)println airport.version

def airport = Airport.get(10)try {

airport.name = "Heathrow"

airport.save(flush:true)

}

catch(org.springframework.dao.OptimisticLockingFailureException e) {

// deal with exception

}Pessimistic Locking

Pessimistic locking is equivalent to doing a SQL "SELECT * FOR UPDATE" statement and locking a row in the database. This has the implication that other read operations will be blocking until the lock is released.In Grails pessimistic locking is performed on an existing instance via the lock method:def airport = Airport.get(10)

airport.lock() // lock for update

airport.name = "Heathrow"

airport.save()

def airport = Airport.lock(10) // lock for update

airport.name = "Heathrow"

airport.save()

Though Grails, through Hibernate, supports pessimistic locking, the embedded HSQLDB shipped with Grails which is used as the default in-memory database does not. If you need to test pessimistic locking you will need to do so against a database that does have support such as MySQL.

GORM supports a number of powerful ways to query from dynamic finders, to criteria to Hibernate's object oriented query language HQL.Groovy's ability to manipulate collections via GPath and methods like sort, findAll and so on combined with GORM results in a powerful combination.However, let's start with the basics.Listing instances

If you simply need to obtain all the instances of a given class you can use the list method:The list method supports arguments to perform pagination:def books = Book.list(offset:10, max:20)

def books = Book.list(sort:"title", order:"asc")

sort argument is the name of the domain class property that you wish to sort on, and the order argument is either asc for ascending or desc for descending.Retrieval by Database Identifier

The second basic form of retrieval is by database identifier using the get method:You can also obtain a list of instances for a set of identifiers using getAll:def books = Book.getAll(23, 93, 81)

Book class:class Book {

String title

Date releaseDate

Author author

}

class Author {

String name

}Book class has properties such as title, releaseDate and author. These can be used by the findBy and findAllBy methods in the form of "method expressions":def book = Book.findByTitle("The Stand")book = Book.findByTitleLike("Harry Pot%")book = Book.findByReleaseDateBetween( firstDate, secondDate )book = Book.findByReleaseDateGreaterThan( someDate )book = Book.findByTitleLikeOrReleaseDateLessThan( "%Something%", someDate )Method Expressions

A method expression in GORM is made up of the prefix such as findBy followed by an expression that combines one or more properties. The basic form is:Book.findBy([Property][Comparator][Boolean Operator])?[Property][Comparator]

def book = Book.findByTitle("The Stand")book = Book.findByTitleLike("Harry Pot%")Like comparator, is equivalent to a SQL like expression.The possible comparators include:

LessThan - less than the given valueLessThanEquals - less than or equal a give valueGreaterThan - greater than a given valueGreaterThanEquals - greater than or equal a given valueLike - Equivalent to a SQL like expressionIlike - Similar to a Like, except case insensitiveNotEqual - Negates equalityBetween - Between two values (requires two arguments)IsNotNull - Not a null value (doesn't require an argument)IsNull - Is a null value (doesn't require an argument)

Notice that the last 3 require different numbers of method arguments compared to the rest, as demonstrated in the following example:def now = new Date()

def lastWeek = now - 7

def book = Book.findByReleaseDateBetween( lastWeek, now )books = Book.findAllByReleaseDateIsNull()

books = Book.findAllByReleaseDateIsNotNull()

Boolean logic (AND/OR)

Method expressions can also use a boolean operator to combine two criteria:def books =

Book.findAllByTitleLikeAndReleaseDateGreaterThan("%Java%", new Date()-30)And in the middle of the query to make sure both conditions are satisfied, but you could equally use Or:def books =

Book.findAllByTitleLikeOrReleaseDateGreaterThan("%Java%", new Date()-30)Querying Associations

Associations can also be used within queries:def author = Author.findByName("Stephen King")def books = author ? Book.findAllByAuthor(author) : []Author instance is not null we use it in a query to obtain all the Book instances for the given Author.Pagination & Sorting

The same pagination and sorting parameters available on the list method can also be used with dynamic finders by supplying a map as the final parameter:def books =

Book.findAllByTitleLike("Harry Pot%", [max:3,

offset:2,

sort:"title",

order:"desc"])def c = Account.createCriteria()

def results = c {

like("holderFirstName", "Fred%")

and {

between("balance", 500, 1000)

eq("branch", "London")

}

maxResults(10)

order("holderLastName", "desc")

}Conjunctions and Disjunctions

As demonstrated in the previous example you can group criteria in a logical AND using a and { } block:and {

between("balance", 500, 1000)

eq("branch", "London")

}or {

between("balance", 500, 1000)

eq("branch", "London")

}not {

between("balance", 500, 1000)

eq("branch", "London")

}Querying Associations

Associations can be queried by having a node that matches the property name. For example say the Account class had many Transaction objects:class Account {

…

def hasMany = [transactions:Transaction]

Set transactions

…

}transaction as a builder node:def c = Account.createCriteria()

def now = new Date()

def results = c.list {

transactions {

between('date',now-10, now)

}

}Account instances that have performed transactions within the last 10 days.

You can also nest such association queries within logical blocks:def c = Account.createCriteria()

def now = new Date()

def results = c.list {

or {

between('created',now-10,now)

transactions {

between('date',now-10, now)

}

}

}Querying with Projections

Projections to be used to customise the results. To use projections you need to define a "projections" node within the criteria builder tree. There are equivalent methods within the projections node to the methods found in the Hibernate Projections class:def c = Account.createCriteria()def numberOfBranches = c.get {

projections {

countDistinct('branch')

}

}Using Scrollable Results

You can use Hibernate's ScrollableResults feature by calling the scroll method:def results = crit.scroll {

maxResults(10)

}

def f = results.first()

def l = results.last()

def n = results.next()

def p = results.previous()def future = results.scroll(10)

def accountNumber = results.getLong('number')

A result iterator that allows moving around within the results by arbitrary increments. The Query / ScrollableResults pattern is very similar to the JDBC PreparedStatement/ ResultSet pattern and the semantics of methods of this interface are similar to the similarly named methods on ResultSet.

Contrary to JDBC, columns of results are numbered from zero.Setting properties in the Criteria instance

If a node within the builder tree doesn't match a particular criterion it will attempt to set a property on the Criteria object itself. Thus allowing full access to all the properties in this class. The below example calls setMaxResults and setFirstResult on the Criteria instance:import org.hibernate.FetchMode as FM

…

def results = c.list {

maxResults(10)

firstResult(50)

fetchMode("aRelationship", FM.EAGER)

}Querying with Eager Fetching

In the section on Eager and Lazy Fetching we discussed how to declaratively specify fetching to avoid the N+1 SELECT problem. However, this can also be achieved using a criteria query:import org.hibernate.FetchMode as FM

...def criteria = Task.createCriteria()

def tasks = criteria.list{

eq("assignee.id", task.assignee.id)

fetchMode('assignee', FM.EAGER)

fetchMode('project', FM.EAGER)

order('priority', 'asc')

}Method Reference

If you invoke the builder with no method name such as:The build defaults to listing all the results and hence the above is equivalent to:| Method | Description |

|---|

|

| list | This is the default method. It returns all matching rows. |

| get | Returns a unique result set, i.e. just one row. The criteria has to be formed that way, that it only queries one row. This method is not to be confused with a limit to just the first row. |

| scroll | Returns a scrollable result set |

| listDistinct | If subqueries or associations are used, one may end up with the same row multiple times in the result set, this allows listing only distinct entities and is equivalent to DISTINCT_ROOT_ENTITY of the CriteriaSpecification class |

GORM classes also support Hibernate's query language HQL, a very complete reference for which can be found Chapter 14. HQL: The Hibernate Query Language of the Hibernate documentation.GORM provides a number of methods that work with HQL including find, findAll and executeQuery. An example of a query can be seen below:def results =

Book.findAll("from Book as b where b.title like 'Lord of the%'")Positional and Named Parameters

In this case the value passed to the query is hard coded, however you can equally use positional parameters:def results =

Book.findAll("from Book as b where b.title like ?", ["The Shi%"])def results =

Book.findAll("from Book as b where b.title like :search or b.author like :search", [search:"The Shi%"])Multiline Queries

If you need to separate the query across multiple lines you can use a line continuation character:def results = Book.findAll("\

from Book as b, \

Author as a \

where b.author = a and a.surname = ?", ['Smith'])

Groovy multiline strings will NOT work with HQL queries

Pagination and Sorting

You can also perform pagination and sorting whilst using HQL queries. To do so simply specify the pagination options as a map at the end of the method call and include an "ORDER BY" clause in the HQL:def results =

Book.findAll("from Book as b where b.title like 'Lord of the%' order by b.title asc",

[max:10, offset:20])The beforeInsert event

Fired before an object is saved to the dbclass Person {

Date dateCreated def beforeInsert = {

dateCreated = new Date()

}

}The beforeUpdate event

Fired before an existing object is updatedclass Person {

Date dateCreated

Date lastUpdated def beforeInsert = {

dateCreated = new Date()

}

def beforeUpdate = {

lastUpdated = new Date()

}

}The beforeDelete event

Fired before an object is deleted.class Person {

String name

Date dateCreated

Date lastUpdated def beforeDelete = {

new ActivityTrace(eventName:"Person Deleted",data:name).save()

}

}The onLoad event

Fired when an object is loaded from the db:class Person {

String name

Date dateCreated

Date lastUpdated def onLoad = {

name = "I'm loaded"

}

}Automatic timestamping

The examples above demonstrated using events to update a lastUpdated and dateCreated property to keep track of updates to objects. However, this is actually not necessary. By merely defining a lastUpdated and dateCreated property these will be automatically updated for you by GORM.If this is not the behaviour you want you can disable this feature with:class Person {

Date dateCreated

Date lastUpdated

static mapping = {

autoTimestamp false

}

}

None if this is necessary if you are happy to stick to the conventions defined by GORM for table, column names and so on. You only needs this functionality if you need to in anyway tailor the way GORM maps onto legacy schemas or performs caching

Custom mappings are defined using a a static mapping block defined within your domain class:class Person {

..

static mapping = { }

}Table names

The database table name which the class maps to can be customized using a call to table:class Person {

..

static mapping = {

table 'people'

}

}people instead of the default name of person.Column names

It is also possible to customize the mapping for individual columns onto the database. For example if its the name you want to change you can do:class Person {

String firstName

static mapping = {

table 'people'

firstName column:'First_Name'

}

}firstName). We then use the named parameter column, to specify the column name to map onto.Column type

GORM supports configuration of Hibernate types via the DSL using the type attribute. This includes specifing user types that subclass the Hibernate org.hibernate.usertype.UserType class, which allows complete customization of how a type is persisted. As an example

if you had a PostCodeType you could use it as follows:class Address {

String number

String postCode

static mapping = {

postCode type:PostCodeType

}

}class Address {

String number

String postCode

static mapping = {

postCode type:'text'

}

}postCode column map to the SQL TEXT or CLOB type depending on which database is being used.See the Hibernate documentation regarding Basic Types for further information.One-to-One Mapping

In the case of associations it is also possible to change the foreign keys used to map associations. In the case of a one-to-one association this is exactly the same as any regular column. For example consider the below:class Person {

String firstName

Address address

static mapping = {

table 'people'

firstName column:'First_Name'

address column:'Person_Adress_Id'

}

}address association would map to a foreign key column called address_id. By using the above mapping we have changed the name of the foreign key column to Person_Adress_Id.One-to-Many Mapping

With a bidirectional one-to-many you can change the foreign key column used simple by changing the column name on the many side of the association as per the example in the previous section on one-to-one associations. However, with unidirectional association the foreign key needs to be specified on the association itself. For example given a unidirectional one-to-many relationship between Person and Address the following code will change the foreign key in the address table:class Person {

String firstName

static hasMany = [addresses:Address]

static mapping = {

table 'people'

firstName column:'First_Name'

addresses column:'Person_Address_Id'

}

}address table, but instead some intermediate join table you can use the joinTable parameter:class Person {

String firstName

static hasMany = [addresses:Address]

static mapping = {

table 'people'

firstName column:'First_Name'

addresses joinTable:[name:'Person_Addresses', key:'Person_Id', column:'Address_Id']

}

}Many-to-Many Mapping

Grails, by default maps a many-to-many association using a join table. For example consider the below many-to-many association:class Group {

…

static hasMany = [people:Person]

}

class Person {

…

static belongsTo = Group

static hasMany = [groups:Group]

}group_person containing foreign keys called person_id and group_id referencing the person and group tables. If you need to change the column names you can specify a column within the mappings for each class.class Group {

…

static mapping = {

people column:'Group_Person_Id'

}

}

class Person {

…

static mapping = {

groups column:'Group_Group_Id'

}

}class Group {

…

static mapping = {

people column:'Group_Person_Id',joinTable:'PERSON_GROUP_ASSOCIATIONS'

}

}

class Person {

…

static mapping = {

groups column:'Group_Group_Id',joinTable:'PERSON_GROUP_ASSOCIATIONS'

}

}Setting up caching

Hibernate features a second-level cache with a customizable cache provider. This needs to be configured in the grails-app/conf/DataSource.groovy file as follows:hibernate {

cache.use_second_level_cache=true

cache.use_query_cache=true

cache.provider_class='org.hibernate.cache.EhCacheProvider'

}

For further reading on caching and in particular Hibernate's second-level cache, refer to the Hibernate documentation on the subject.

Caching instances

In your mapping block to enable caching with the default settings use a call to the cache method:class Person {

..

static mapping = {

table 'people'

cache true

}

}class Person {

..

static mapping = {

table 'people'

cache usage:'read-only', include:'non-lazy'

}

}Caching associations

As well as the ability to use Hibernate's second level cache to cache instances you can also cache collections (associations) of objects. For example:class Person {

String firstName

static hasMany = [addresses:Address]

static mapping = {

table 'people'

version false

addresses column:'Address', cache:true

}

}

class Address {

String number

String postCode

}cache:'read-write' // or 'read-only' or 'transactional'

Cache usages

Below is a description of the different cache settings and their usages:

read-only - If your application needs to read but never modify instances of a persistent class, a read-only cache may be used.read-write - If the application needs to update data, a read-write cache might be appropriate.nonstrict-read-write - If the application only occasionally needs to update data (ie. if it is extremely unlikely that two transactions would try to update the same item simultaneously) and strict transaction isolation is not required, a nonstrict-read-write cache might be appropriate.transactional - The transactional cache strategy provides support for fully transactional cache providers such as JBoss TreeCache. Such a cache may only be used in a JTA environment and you must specify hibernate.transaction.manager_lookup_class in the grails-app/conf/DataSource.groovy file's hibernate config.

By default GORM classes uses table-per-hierarchy inheritance mapping. This has the disadvantage that columns cannot have a NOT-NULL constraint applied to them at the db level. If you would prefer to use a table-per-subclass inheritance strategy you can do so as follows:class Payment {

Long id

Long version

Integer amount static mapping = {

tablePerHierarchy false

}

}

class CreditCardPayment extends Payment {

String cardNumber

}Payment class specifies that it will not be using table-per-hierarchy mapping for all child classes.You can customize how GORM generates identifiers for the database using the DSL. By default GORM relies on the native database mechanism for generating ids. This is by far the best approach, but there are still many schemas that have different approaches to identity.To deal with this Hibernate defines the concept of an id generator. You can customize the id generator and the column it maps to as follows:class Person {

..

static mapping = {

table 'people'

version false

id generator:'hilo', params:[table:'hi_value',column:'next_value',max_lo:100]

}

}

For more information on the different Hibernate generators refer to the Hibernate reference documentation

Note that if you want to merely customise the column that the id lives on you can do:class Person {

..

static mapping = {

table 'people'

version false

id column:'person_id'

}

}class Person {

String firstName

String lastName static mapping = {

id composite:['firstName', 'lastName']

}

}firstName and lastName properties of the Person class. When you later need to retrieve an instance by id you have to use a prototype of the object itself:def p = Person.get(new Person(firstName:"Fred", lastName:"Flintstone"))

println p.firstName

class Person {

String firstName

String address

static mapping = {

table 'people'

version false

id column:'person_id'

firstName column:'First_Name', index:'Name_Idx'

address column:'Address', index:'Name_Idx, Address_Index'

}

}version property into every class which is in turn mapped to a version column at the database level.If you're mapping to a legacy schema this can be problematic, so you can disable this feature by doing the following:class Person {

..

static mapping = {

table 'people'

version false

}

}

If you disable optimistic locking you are essentially on your own with regards to concurrent updates and are open to the risk of users losing (due to data overriding) data unless you use pessimistic locking

Lazy Collections

As discussed in the section on Eager and Lazy fetching, by default GORM collections use lazy fetching and is is configurable through the fetchMode setting. However, if you prefer to group all your mappings together inside the mappings block you can also use the ORM DSL to configure fetching:class Person {

String firstName

static hasMany = [addresses:Address]

static mapping = {

addresses lazy:false

}

}

class Address {

String street

String postCode

}Lazy Single-Ended Associations

In GORM, one-to-one and many-to-one associations are by default non-lazy. This can be problematic in cases when you are loading many entities which have an association to another entity as a new SELECT statement is executed for each loaded entity. You can make one-to-one and many-to-one associations lazy using the same technique as for lazy collections:class Person {

String firstName

static belongsTo = [address:Address]

static mapping = {

address lazy:true // lazily fetch the address

}

}

class Address {

String street

String postCode

}address property of the Person class to be lazily loaded.As describes in the section on cascading updates, the primary mechanism to control the way updates and deletes are cascading from one association to another is the belongsTo static property.However, the ORM DSL gives you complete access to Hibernate's transitive persistence capabilities via the cascade attribute.Valid settings for the cascade attribute include:

- create - cascades creation of new records from one association to another

- merge - merges the state of a detached association

- save-update - cascades only saves and updates to an association

- delete - cascades only deletes to an association

- lock - useful if a pessimistic lock should be cascaded to its associations

- refresh - cascades refreshes to an association

- evict - cascades evictions (equivalent to discard() in GORM) to associations if set

- all - cascade ALL operations to associations

- delete-orphan - Applies only to one-to-many associations and indicates that when a child is removed from an association then it should be automatically deleted

It is advisable to read the section in the Hibernate documentation on transitive persistence to obtain a better understanding of the different cascade styles and recommendation for their usage

To specific the cascade attribute simply define one or many (comma-separated) of the aforementioned settings as its value:class Person {

String firstName

static hasMany = [addresses:Address]

static mapping = {

addresses cascade:"all,delete-orphan"

}

}

class Address {

String street

String postCode

}def transferFunds = {

Account.withTransaction { status ->

def source = Account.get(params.from)

def dest = Account.get(params.to) def amount = params.amount.toInteger()

if(source.active) {

source.balance -= amount

if(dest.active) {

dest.amount += amount

}

else {

status.setRollbackOnly()

}

}

}}String name

String description

column name | data type

description | varchar(255)

column name | data type

description | TEXT

static constraints = {

description(maxSize:1000)

}Constraints Affecting String Properties

If either the maxSize or the size constraint is defined, Grails sets the maximum column length based on the constraint value.In general, it's not advisable to use both constraints on the same domain class property. However, if both the maxSize constraint and the size constraint are defined, then Grails sets the column length to the minimum of the maxSize constraint and the upper bound of the size constraint. (Grails uses the minimum of the two, because any length that exceeds that minimum will result in a validation error.)If the inList constraint is defined (and the maxSize and the size constraints are not defined), then Grails sets the maximum column length based on the length of the longest string in the list of valid values. For example, given a list including values "Java", "Groovy", and "C++", Grails would set the column length to 6 (i.e., the number of characters in the string "Groovy").Constraints Affecting Numeric Properties

If the max constraint, the min constraint, or the range constraint is defined, Grails attempts to set the column precision based on the constraint value. (The success of this attempted influence is largely dependent on how Hibernate interacts with the underlying DBMS.)In general, it's not advisable to combine the pair min/max and range constraints together on the same domain class property. However, if both of these constraints is defined, then Grails uses the minimum precision value from the constraints. (Grails uses the minimum of the two, because any length that exceeds that minimum precision will result in a validation error.)

If the scale constraint is defined, then Grails attempts to set the column scale based on the constraint value. This rule only applies to floating point numbers (i.e., java.lang.Float, java.Lang.Double, java.lang.BigDecimal, or subclasses of java.lang.BigDecimal). (The success of this attempted influence is largely dependent on how Hibernate interacts with the underlying DBMS.)The constraints define the minimum/maximum numeric values, and Grails derives the maximum number of digits for use in the precision. Keep in mind that specifying only one of min/max constraints will not affect schema generation (since there could be large negative value of property with max:100, for example), unless specified constraint value requires more digits than default Hibernate column precision is (19 at the moment). For example...someFloatValue(max:1000000, scale:3)

someFloatValue DECIMAL(19, 3) // precision is default

someFloatValue(max:12345678901234567890, scale:5)

someFloatValue DECIMAL(25, 5) // precision = digits in max + scale

someFloatValue(max:100, min:-100000)

someFloatValue DECIMAL(8, 2) // precision = digits in min + default scale